-

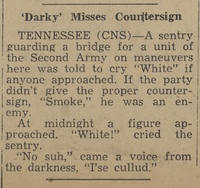

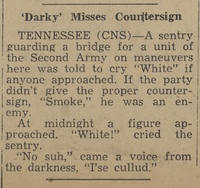

" 'Darky' Misses Countersign"

" 'Darky' Misses Countersign" Article published in the Camp Howze Howitzer.

-

Double V Campaign

Double V Campaign A digital image of the original Double VV Campaign launched and promoted by the Pittsburgh Courier, suggested by James G. Thompson, in a letter he wrote to the editor of the newspaper.

-

"Don't Want Negro Soldiers"

"Don't Want Negro Soldiers" An article in the Denton Record-Chronicle about local small towns requesting the government not send them black soldiers.

-

"Seek Center for Negro Soldiers"

"Seek Center for Negro Soldiers" An article in the Denton Record-Chronicle about the efforts of black community members in Denton to have the city address its lack of recreational facilities available for visiting black soldiers.

-

Racist "joke"

Racist "joke" A demeaning portrayal of black soldiers published in the Denton Record-Chronicle intended as a joke.

-

"Denton Negro Soldier Reenlists"

"Denton Negro Soldier Reenlists" Article in the Denton Record-Chronicle announcing that George Pollard, after serving in the Army for three years, had reenlisted in the military to serve in the Army Air Forces.

-

"A Story from the Other World War"

"A Story from the Other World War" A racist portrayal of black soldiers was published as a joke in the Denton Record-Chronicle.

-

"Papers from Home"

"Papers from Home" Photograph published in the Camp Howze Howitzer of "white" soldiers enjoying free and easy access to their preferred news publications.

-

"Colored Citizens Observe Holiday"

"Colored Citizens Observe Holiday" An article about black Gainesville residents coordinating with the local USO for black Camp Howze soldiers to celebrate the emancipation of people who had been enslaved in Texas.

-

"GI Fun for This Week"

"GI Fun for This Week" A schedule of USO activities was published in the Camp Howze Howitzer for each of the three service clubs.

-

"Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Private Smith, a Black WWII Soldier

"Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Private Smith, a Black WWII Soldier In this 1942 recording, a black U.S. Army soldier, identified as Private Smith, stationed at Camp Polk, LA describes at great length, the widespread racism, discrimination, and degrading mistreatment that black service members endured each day from military members and civilians despite serving the country honorably with the hope of creating a better future for America.

Transcript:

00:14-07:34 “Mr. President, I am a Negro private in the United States Army. I’m a native of Austin, Texas. Thinking that you might be interested in the life of a Negro soldier and the treatment he gets in the United States Army. I was glad to have this opportunity to bring you some of the facts as I see them today. The negro soldier as a whole believes that he has something to fight for and believes in the outcome he will have more to fight for than he has now. But at the present time the Negro is treated with some discrimination in the army. It is probably because of the fact that the superior officers do not realize the sentiment that the Negro has. He feels that he has as much to fight for as any other man, but he do not like the treatment that the other people give him because at time they treat him with an inferior complex. The Negro realizes that in the past he has not got the promises that was made to him in the Declaration of Independence or in the Declaration of the Emancipation of slaves. Because at times the Negro is treated as he was before these things happened. Today the Negro fear that probably he has to fight for the promises that was made and it seem like sometime that these promises is all that he has to fight for because in the time that has passed they had not come into reality. But the Negro hopes that when these things are over, when the war is over, that these promises that had been made to him, the promises that he’s fighting for, the promises that he lives and hopes for, will all be a reality. We know, Mr. President, that you have not time to get out among these people and see the things that goes on and see the different actions and attitudes that people have towards the Negro soldier. In some states it is better than others. Especially in the southern states it is very bad. Of course, the southern state is Jim Crow but the Negro feel that when he is in the United States Army that he [sic] to be considered as never before or part of the United States and should not be treated as a dog or some other animal with such an inferiority complex because afterall the Negro, when he is in the army, is serving the same purpose that any other man is serving. He has the same duties to fear that any other man has to fear. And he feels that when he is in the service he should be given as much consideration as any other man. In the long run, the Negro feel that these things will come about because the Negro has faith in the President of the United States and the things that he stands for. And he believes deep down in his heart that the President of the United States do not believe in the way that the Negro is treated is right. And he hopes in the long run, the president will be able to do something about it. Of course, he know he’ll have to have cooperation of the Negro. The Negro is ready to give that. I’m stationed in Camp Polk, Louisiana. At the present time race discrimination is very bad. It’s not so bad in the army. Of course some things happen that shows that people still have that thing within ‘em that makes ‘em look upon the Negro as something that’s not human or something of that kind. But in the southern states the people, the civilian people, are very much so against the Negro and the Negro in uniform that at times it seems like they’d rather not have the Negro in the service. But the Negro feel and the Negro will, after all these treatments, do as much for this country as any other man, and that is give up his life because he feel like there’s tomorrow and tomorrow will bring the things that he has hoped and prayed for. I feel that I voiced the sentiment of every colored man and I’m really speaking from the depths of my heart that no man can do any more for the United States than I can. No man can fight harder for victory than I can. No man can do more to bring about the safeness of this country and the loved ones and the friends we have here than I can. And I feel like every soldier, every colored soldier, in the United States Army, feel within himself exactly as I do because after all, of whatever any man do, he can’t do anymore than give up his life. And that’s what every colored soldier in the United States Army that the flag waves over, that wears the United States colors, he feel like he has only one life to live and if it takes that life to make this country safe for democracy and the things that he hoped for and the things that has been promised to him, he’s ready to give up his life. He knows that he may not enjoy these things. He may not be able to see these things happen, may not see these things come about, but he realize in the future he have loved ones that he left behind at home and he has friends that he would like to see enjoy these blessings and he is ready to give up his life to make these things possible.”

-

"Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recording of David Helfeld, New York city college student

"Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recording of David Helfeld, New York city college student David Helfeld, a 19-year-old college student and the President of the Student Council at the College of the City of New York, speaks on behalf of himself and his fellow students regarding their mutual horror over the discrimination against Black Americans in the United States Armed Forces. He equates the mistreatment of Black Americans with the same fascism being fought by Americans overseas and insists it must be fought at home as well.

Transcript:

01:04-02:59 “...Dear Mr. President, My name is David Helfeld…I happen to have the honor to be the President of the Student Council of College of the City of New York. I’m only 19 now and I have a year before I graduate. Before I become 20 I intend to join the army. There’s just one thought I’d like to get across to you. It’s a feeling which horrifies all the boys at our college and that is negro discrimination in the army and in the navy. It seems to me to be an example, a very horrible example of fascism within democracy. When we here at the college hear that there are … purely Negro regiments and that Negroes are only allowed to do slop duty aboard the ships of our navy, it makes us feel very bad. We here realize that there are three wars to be fought; the physical war against the fascist nations - Germany, Italy, and Japan, and the war from within against anti-semitism, Jim Crow, and factors of that nature. We feel that as long as we have fascism at home it is rather futile to fight from the outside if we are not at the same time fighting it from within. I thank you for listening. Besides the two wars I’ve just mentioned I feel there is a third war, a very important one, namely the war to make a proper peace, peace which will do away with all wars in the future.”

-

"Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket

"Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket Audio recording jacket for 1942 interview of Black Americans in Nashville, TN with handwritten descriptions of persons interviewed.

-

"Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recorded Interviews of Black Americans in Nashville, TN

"Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recorded Interviews of Black Americans in Nashville, TN 00:10-01:20 Black American lawyer, Alexander Luvey, argued against the federal government entrusting racist local governments with the authority to oversee the administration of federal benefits for Black Americans.

Transcript:

“Mr. President, this is Alexander Luvey, a lawyer from Nashville, Tennessee. It is generally recognized that the Negroes of the South are not contributing as much as they can contribute to his national defense. Nor are they receiving the benefits which the federal government desires them to receive. This is due to the fact that the federal government is working through constituted local authorities. It is true that local served government is a theory of democratic government, but Mr. President, this is a condition and not a theory which confronts us Negroes in the South. When the head of our government publically announces that this is a white man's country, when the head of our local Department of Education fights vigorously to maintain a dual educational system paying different salary schedules, how can we expect that the local authorities will function fairly and efficiently for the Negro?...”

-

"Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Black Americans in Nashville, TN, 1942

"Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Black Americans in Nashville, TN, 1942 00:08-01:31, 01:36-02:42 Recorded interviews with several Black Americans from Nashville, TN addressing President Roosevelt with their concerns regarding discrimination against black citizens and abuse of black servicemen. The Nashville residents interviewed asked President Roosevelt for his understanding and assistance in protecting the rights of black citizens to serve their country.

Transcript:

“...I am thinking of 15 million Negroes who are among the most loyal citizens in the United States. In the face of discrimination and segregation the Negro has remained loyal. What greater proof than a Joe Louis benefit for the navy, a branch of our armed services which has never permitted his race to rise above the ships galley. These millions of negroes are doing all in their power to serve in the presence crisis. Most defense industries are closed to him. The possibility of advancement in the army is definitely limited. If Democracy is to survive. If Democracy is ever to be made to work, our generation must make it work. We want as you do, to perpetuate the democratic way of life. Do all in your power as we are doing to remove the barriers, raise the ceilings, unshackle the loyalties, release the energies and the initiative of this loyal race that together, all Americans, all liberty loving peoples may give their all that our way of life may survive.”

01:36-2:42 Mrs. Julia T. Glavin of Nashville, TN. “Mr. President, in this section of the United States it seems to me that there are two outstanding problems confronting us now. They have to do with our negro soldiers and taxation. In certain parts of our country the uniform of our army is not properly respected. Our loyal black boys in uniform should be protected while they’re in camp. The ruthless beating up and murdering of them should be stopped. This sort of thing breaks down the morale of any army. Every loyal soldier is an important factor in our defense program. It’ll take a lot of money to win this war. We’re going to win and we’re going to sacrifice all we have for our country, but it has become a problem to know how to meet these new taxes and keep up the old ones with our limited incomes which have not increased with the increased demand of heavy taxation. If we borrow we are plunged into debt, and citizens in debt cannot present as strong a defense as we desire, but we have pledged ourselves to do our best.”

-

"Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket

"Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket Audio Jacket for "Dear Mr. President" interview of black residents in Nashville, TN during the winter of 1942.

-

Sergeant Joseph H. Ward

Sergeant Joseph H. Ward An announcement in The Oklahoma Eagle, a black newspaper, honoring the military service of Sgt. James H. Ward, recently transferred from Camp Howze, TX to Camp Claiborne, LA as a member of the U.S. Army Service Force.

-

"Dear Mr. President" by Miss Maude Gray

"Dear Mr. President" by Miss Maude Gray In this recording, Miss Maude Gray of Austin, TX relays her concerns regarding the mistreatment and discrimination black soldiers, like her brother, were forced to endure as service members in the U.S. military. She asks President Roosevelt to understand that black Americans want to serve in the military honorably. She explains why black Americans need the president's help to ensure they are treated with dignity and offered the same opportunities to serve their country as all willing, able-bodied Americans.

Transcript:

Miss Maude Gray speaks about her brother and other black soldiers’ experience with racist treatment in the military and by authorities unwilling to hire them. “…I got a brother who’s in the army….when he left here he was mighty glad to get in the army. I don’t know whether he’s so glad to be there now from all the letters I’ve been gettin from him. Mind you, I don’t mean that he’s against our country or anything like that, but he’s not so satisfied with the treatment that he’s gettin up there, he thinks that it could be a little better….” The young woman goes on to describe degrading mistreatment of her brother and his fellow black soldiers. She mentions public fears of race riots as the justification for keeping black soldiers from accessing and training with weapons. “They don’t have any entertainment for them, whereas the white soldiers have lounges, and guest houses, and everything that they could wish for as far as facilities will permit while our boys don’t have anything but a post exchange. And that’s not very good for entertainment and when that’s all he has to do. I think they could stand that if they were just treated a little better when it comes to other things that are most important duties, promotions. The navy won’t let you in. The army, when they get you, it put you off somewhere off by yourself…”

-

Miss Maude Gray, "Negro Girl from Austin, Texas"

Miss Maude Gray, "Negro Girl from Austin, Texas" Jacket for the recording of Miss Gray in which she relays her concerns regarding the mistreatment and discrimination black soldiers, like her brother, were forced to endure as service members in the U.S. military. She asks President Roosevelt to understand that black Americans want to serve in the military honorably. She explains why black Americans need his help to ensure they are treated with dignity and offered the same opportunities as everyone else.

-

Gainesville Negro Girl Lieutenant

Gainesville Negro Girl Lieutenant This brief mention of a young black woman's commission as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps was a rare moment of acknowledgment for black service members in news publications covering the local region surrounding Camp Howze

-

Response from Mr. Gibson,

Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War

Response from Mr. Gibson,

Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War In this response letter to Private E.L. Reynolds, Mr. Gibson, implies that banning the Pittsburgh Courier, or any other "Negro publication" at Camp Howze would violate official War Department policy AG 461 Subject: Restriction of Commercial Publications. Mr. Gibson advises Pvt. Reynolds to write back with further details regarding this issue.

-

Black Newspapers Banned at Camp Howze

Black Newspapers Banned at Camp Howze A letter from a black soldier at Camp Howze to Truman K. Gibson, Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War, in which the soldier asks why the camp's post exchange for black servicemen will not sell the Pittsburgh Courier, a highly regarded black newspaper. This was significant because news reports in local publications including the Camp Howze Howitzer rarely included stories of black citizens or service members, choosing instead to report exclusively on white Americans' experiences and perspectives that often demeaned black Americans.

-

The Wolf - Untitled Camp Howze Howitzer Comic

The Wolf - Untitled Camp Howze Howitzer Comic Racist imagery used for humor in the Camp Howze Howitzer.

-

"I Made $1.35 in Tips Yesterday"

"I Made $1.35 in Tips Yesterday" Racist depiction of African men dressed in loin cloth and carrying the white soldiers’ goods.

-

Camp Howze Howitzer Comic

Camp Howze Howitzer Comic Comic illustration depicting a topless African woman looming over U.S. soldiers in a threatening manner.

-

Blackface Performance at Camp Howze

Blackface Performance at Camp Howze Photo of servicemen from the 409th Infantry regiment dressed in blackface and costume posed to advertise a performance planned to entertain GIs at Camp Howze.

-

"Minstrel Darky Doings"

"Minstrel Darky Doings" Photograph of white servicemen from the 84th Infantry Division Special Service performing in blackface as minstrels to entertain GIs at Camp Howze.

" 'Darky' Misses Countersign" Article published in the Camp Howze Howitzer.

" 'Darky' Misses Countersign" Article published in the Camp Howze Howitzer. Double V Campaign A digital image of the original Double VV Campaign launched and promoted by the Pittsburgh Courier, suggested by James G. Thompson, in a letter he wrote to the editor of the newspaper.

Double V Campaign A digital image of the original Double VV Campaign launched and promoted by the Pittsburgh Courier, suggested by James G. Thompson, in a letter he wrote to the editor of the newspaper. "Don't Want Negro Soldiers" An article in the Denton Record-Chronicle about local small towns requesting the government not send them black soldiers.

"Don't Want Negro Soldiers" An article in the Denton Record-Chronicle about local small towns requesting the government not send them black soldiers. "Seek Center for Negro Soldiers" An article in the Denton Record-Chronicle about the efforts of black community members in Denton to have the city address its lack of recreational facilities available for visiting black soldiers.

"Seek Center for Negro Soldiers" An article in the Denton Record-Chronicle about the efforts of black community members in Denton to have the city address its lack of recreational facilities available for visiting black soldiers. Racist "joke" A demeaning portrayal of black soldiers published in the Denton Record-Chronicle intended as a joke.

Racist "joke" A demeaning portrayal of black soldiers published in the Denton Record-Chronicle intended as a joke. "Denton Negro Soldier Reenlists" Article in the Denton Record-Chronicle announcing that George Pollard, after serving in the Army for three years, had reenlisted in the military to serve in the Army Air Forces.

"Denton Negro Soldier Reenlists" Article in the Denton Record-Chronicle announcing that George Pollard, after serving in the Army for three years, had reenlisted in the military to serve in the Army Air Forces. "A Story from the Other World War" A racist portrayal of black soldiers was published as a joke in the Denton Record-Chronicle.

"A Story from the Other World War" A racist portrayal of black soldiers was published as a joke in the Denton Record-Chronicle. "Papers from Home" Photograph published in the Camp Howze Howitzer of "white" soldiers enjoying free and easy access to their preferred news publications.

"Papers from Home" Photograph published in the Camp Howze Howitzer of "white" soldiers enjoying free and easy access to their preferred news publications. "Colored Citizens Observe Holiday" An article about black Gainesville residents coordinating with the local USO for black Camp Howze soldiers to celebrate the emancipation of people who had been enslaved in Texas.

"Colored Citizens Observe Holiday" An article about black Gainesville residents coordinating with the local USO for black Camp Howze soldiers to celebrate the emancipation of people who had been enslaved in Texas. "GI Fun for This Week" A schedule of USO activities was published in the Camp Howze Howitzer for each of the three service clubs.

"GI Fun for This Week" A schedule of USO activities was published in the Camp Howze Howitzer for each of the three service clubs. "Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Private Smith, a Black WWII Soldier In this 1942 recording, a black U.S. Army soldier, identified as Private Smith, stationed at Camp Polk, LA describes at great length, the widespread racism, discrimination, and degrading mistreatment that black service members endured each day from military members and civilians despite serving the country honorably with the hope of creating a better future for America. Transcript: 00:14-07:34 “Mr. President, I am a Negro private in the United States Army. I’m a native of Austin, Texas. Thinking that you might be interested in the life of a Negro soldier and the treatment he gets in the United States Army. I was glad to have this opportunity to bring you some of the facts as I see them today. The negro soldier as a whole believes that he has something to fight for and believes in the outcome he will have more to fight for than he has now. But at the present time the Negro is treated with some discrimination in the army. It is probably because of the fact that the superior officers do not realize the sentiment that the Negro has. He feels that he has as much to fight for as any other man, but he do not like the treatment that the other people give him because at time they treat him with an inferior complex. The Negro realizes that in the past he has not got the promises that was made to him in the Declaration of Independence or in the Declaration of the Emancipation of slaves. Because at times the Negro is treated as he was before these things happened. Today the Negro fear that probably he has to fight for the promises that was made and it seem like sometime that these promises is all that he has to fight for because in the time that has passed they had not come into reality. But the Negro hopes that when these things are over, when the war is over, that these promises that had been made to him, the promises that he’s fighting for, the promises that he lives and hopes for, will all be a reality. We know, Mr. President, that you have not time to get out among these people and see the things that goes on and see the different actions and attitudes that people have towards the Negro soldier. In some states it is better than others. Especially in the southern states it is very bad. Of course, the southern state is Jim Crow but the Negro feel that when he is in the United States Army that he [sic] to be considered as never before or part of the United States and should not be treated as a dog or some other animal with such an inferiority complex because afterall the Negro, when he is in the army, is serving the same purpose that any other man is serving. He has the same duties to fear that any other man has to fear. And he feels that when he is in the service he should be given as much consideration as any other man. In the long run, the Negro feel that these things will come about because the Negro has faith in the President of the United States and the things that he stands for. And he believes deep down in his heart that the President of the United States do not believe in the way that the Negro is treated is right. And he hopes in the long run, the president will be able to do something about it. Of course, he know he’ll have to have cooperation of the Negro. The Negro is ready to give that. I’m stationed in Camp Polk, Louisiana. At the present time race discrimination is very bad. It’s not so bad in the army. Of course some things happen that shows that people still have that thing within ‘em that makes ‘em look upon the Negro as something that’s not human or something of that kind. But in the southern states the people, the civilian people, are very much so against the Negro and the Negro in uniform that at times it seems like they’d rather not have the Negro in the service. But the Negro feel and the Negro will, after all these treatments, do as much for this country as any other man, and that is give up his life because he feel like there’s tomorrow and tomorrow will bring the things that he has hoped and prayed for. I feel that I voiced the sentiment of every colored man and I’m really speaking from the depths of my heart that no man can do any more for the United States than I can. No man can fight harder for victory than I can. No man can do more to bring about the safeness of this country and the loved ones and the friends we have here than I can. And I feel like every soldier, every colored soldier, in the United States Army, feel within himself exactly as I do because after all, of whatever any man do, he can’t do anymore than give up his life. And that’s what every colored soldier in the United States Army that the flag waves over, that wears the United States colors, he feel like he has only one life to live and if it takes that life to make this country safe for democracy and the things that he hoped for and the things that has been promised to him, he’s ready to give up his life. He knows that he may not enjoy these things. He may not be able to see these things happen, may not see these things come about, but he realize in the future he have loved ones that he left behind at home and he has friends that he would like to see enjoy these blessings and he is ready to give up his life to make these things possible.”

"Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Private Smith, a Black WWII Soldier In this 1942 recording, a black U.S. Army soldier, identified as Private Smith, stationed at Camp Polk, LA describes at great length, the widespread racism, discrimination, and degrading mistreatment that black service members endured each day from military members and civilians despite serving the country honorably with the hope of creating a better future for America. Transcript: 00:14-07:34 “Mr. President, I am a Negro private in the United States Army. I’m a native of Austin, Texas. Thinking that you might be interested in the life of a Negro soldier and the treatment he gets in the United States Army. I was glad to have this opportunity to bring you some of the facts as I see them today. The negro soldier as a whole believes that he has something to fight for and believes in the outcome he will have more to fight for than he has now. But at the present time the Negro is treated with some discrimination in the army. It is probably because of the fact that the superior officers do not realize the sentiment that the Negro has. He feels that he has as much to fight for as any other man, but he do not like the treatment that the other people give him because at time they treat him with an inferior complex. The Negro realizes that in the past he has not got the promises that was made to him in the Declaration of Independence or in the Declaration of the Emancipation of slaves. Because at times the Negro is treated as he was before these things happened. Today the Negro fear that probably he has to fight for the promises that was made and it seem like sometime that these promises is all that he has to fight for because in the time that has passed they had not come into reality. But the Negro hopes that when these things are over, when the war is over, that these promises that had been made to him, the promises that he’s fighting for, the promises that he lives and hopes for, will all be a reality. We know, Mr. President, that you have not time to get out among these people and see the things that goes on and see the different actions and attitudes that people have towards the Negro soldier. In some states it is better than others. Especially in the southern states it is very bad. Of course, the southern state is Jim Crow but the Negro feel that when he is in the United States Army that he [sic] to be considered as never before or part of the United States and should not be treated as a dog or some other animal with such an inferiority complex because afterall the Negro, when he is in the army, is serving the same purpose that any other man is serving. He has the same duties to fear that any other man has to fear. And he feels that when he is in the service he should be given as much consideration as any other man. In the long run, the Negro feel that these things will come about because the Negro has faith in the President of the United States and the things that he stands for. And he believes deep down in his heart that the President of the United States do not believe in the way that the Negro is treated is right. And he hopes in the long run, the president will be able to do something about it. Of course, he know he’ll have to have cooperation of the Negro. The Negro is ready to give that. I’m stationed in Camp Polk, Louisiana. At the present time race discrimination is very bad. It’s not so bad in the army. Of course some things happen that shows that people still have that thing within ‘em that makes ‘em look upon the Negro as something that’s not human or something of that kind. But in the southern states the people, the civilian people, are very much so against the Negro and the Negro in uniform that at times it seems like they’d rather not have the Negro in the service. But the Negro feel and the Negro will, after all these treatments, do as much for this country as any other man, and that is give up his life because he feel like there’s tomorrow and tomorrow will bring the things that he has hoped and prayed for. I feel that I voiced the sentiment of every colored man and I’m really speaking from the depths of my heart that no man can do any more for the United States than I can. No man can fight harder for victory than I can. No man can do more to bring about the safeness of this country and the loved ones and the friends we have here than I can. And I feel like every soldier, every colored soldier, in the United States Army, feel within himself exactly as I do because after all, of whatever any man do, he can’t do anymore than give up his life. And that’s what every colored soldier in the United States Army that the flag waves over, that wears the United States colors, he feel like he has only one life to live and if it takes that life to make this country safe for democracy and the things that he hoped for and the things that has been promised to him, he’s ready to give up his life. He knows that he may not enjoy these things. He may not be able to see these things happen, may not see these things come about, but he realize in the future he have loved ones that he left behind at home and he has friends that he would like to see enjoy these blessings and he is ready to give up his life to make these things possible.” "Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recording of David Helfeld, New York city college student David Helfeld, a 19-year-old college student and the President of the Student Council at the College of the City of New York, speaks on behalf of himself and his fellow students regarding their mutual horror over the discrimination against Black Americans in the United States Armed Forces. He equates the mistreatment of Black Americans with the same fascism being fought by Americans overseas and insists it must be fought at home as well. Transcript: 01:04-02:59 “...Dear Mr. President, My name is David Helfeld…I happen to have the honor to be the President of the Student Council of College of the City of New York. I’m only 19 now and I have a year before I graduate. Before I become 20 I intend to join the army. There’s just one thought I’d like to get across to you. It’s a feeling which horrifies all the boys at our college and that is negro discrimination in the army and in the navy. It seems to me to be an example, a very horrible example of fascism within democracy. When we here at the college hear that there are … purely Negro regiments and that Negroes are only allowed to do slop duty aboard the ships of our navy, it makes us feel very bad. We here realize that there are three wars to be fought; the physical war against the fascist nations - Germany, Italy, and Japan, and the war from within against anti-semitism, Jim Crow, and factors of that nature. We feel that as long as we have fascism at home it is rather futile to fight from the outside if we are not at the same time fighting it from within. I thank you for listening. Besides the two wars I’ve just mentioned I feel there is a third war, a very important one, namely the war to make a proper peace, peace which will do away with all wars in the future.”

"Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recording of David Helfeld, New York city college student David Helfeld, a 19-year-old college student and the President of the Student Council at the College of the City of New York, speaks on behalf of himself and his fellow students regarding their mutual horror over the discrimination against Black Americans in the United States Armed Forces. He equates the mistreatment of Black Americans with the same fascism being fought by Americans overseas and insists it must be fought at home as well. Transcript: 01:04-02:59 “...Dear Mr. President, My name is David Helfeld…I happen to have the honor to be the President of the Student Council of College of the City of New York. I’m only 19 now and I have a year before I graduate. Before I become 20 I intend to join the army. There’s just one thought I’d like to get across to you. It’s a feeling which horrifies all the boys at our college and that is negro discrimination in the army and in the navy. It seems to me to be an example, a very horrible example of fascism within democracy. When we here at the college hear that there are … purely Negro regiments and that Negroes are only allowed to do slop duty aboard the ships of our navy, it makes us feel very bad. We here realize that there are three wars to be fought; the physical war against the fascist nations - Germany, Italy, and Japan, and the war from within against anti-semitism, Jim Crow, and factors of that nature. We feel that as long as we have fascism at home it is rather futile to fight from the outside if we are not at the same time fighting it from within. I thank you for listening. Besides the two wars I’ve just mentioned I feel there is a third war, a very important one, namely the war to make a proper peace, peace which will do away with all wars in the future.” "Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket Audio recording jacket for 1942 interview of Black Americans in Nashville, TN with handwritten descriptions of persons interviewed.

"Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket Audio recording jacket for 1942 interview of Black Americans in Nashville, TN with handwritten descriptions of persons interviewed. "Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recorded Interviews of Black Americans in Nashville, TN 00:10-01:20 Black American lawyer, Alexander Luvey, argued against the federal government entrusting racist local governments with the authority to oversee the administration of federal benefits for Black Americans. Transcript: “Mr. President, this is Alexander Luvey, a lawyer from Nashville, Tennessee. It is generally recognized that the Negroes of the South are not contributing as much as they can contribute to his national defense. Nor are they receiving the benefits which the federal government desires them to receive. This is due to the fact that the federal government is working through constituted local authorities. It is true that local served government is a theory of democratic government, but Mr. President, this is a condition and not a theory which confronts us Negroes in the South. When the head of our government publically announces that this is a white man's country, when the head of our local Department of Education fights vigorously to maintain a dual educational system paying different salary schedules, how can we expect that the local authorities will function fairly and efficiently for the Negro?...”

"Dear Mr. President" 1942 Recorded Interviews of Black Americans in Nashville, TN 00:10-01:20 Black American lawyer, Alexander Luvey, argued against the federal government entrusting racist local governments with the authority to oversee the administration of federal benefits for Black Americans. Transcript: “Mr. President, this is Alexander Luvey, a lawyer from Nashville, Tennessee. It is generally recognized that the Negroes of the South are not contributing as much as they can contribute to his national defense. Nor are they receiving the benefits which the federal government desires them to receive. This is due to the fact that the federal government is working through constituted local authorities. It is true that local served government is a theory of democratic government, but Mr. President, this is a condition and not a theory which confronts us Negroes in the South. When the head of our government publically announces that this is a white man's country, when the head of our local Department of Education fights vigorously to maintain a dual educational system paying different salary schedules, how can we expect that the local authorities will function fairly and efficiently for the Negro?...” "Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Black Americans in Nashville, TN, 1942 00:08-01:31, 01:36-02:42 Recorded interviews with several Black Americans from Nashville, TN addressing President Roosevelt with their concerns regarding discrimination against black citizens and abuse of black servicemen. The Nashville residents interviewed asked President Roosevelt for his understanding and assistance in protecting the rights of black citizens to serve their country. Transcript: “...I am thinking of 15 million Negroes who are among the most loyal citizens in the United States. In the face of discrimination and segregation the Negro has remained loyal. What greater proof than a Joe Louis benefit for the navy, a branch of our armed services which has never permitted his race to rise above the ships galley. These millions of negroes are doing all in their power to serve in the presence crisis. Most defense industries are closed to him. The possibility of advancement in the army is definitely limited. If Democracy is to survive. If Democracy is ever to be made to work, our generation must make it work. We want as you do, to perpetuate the democratic way of life. Do all in your power as we are doing to remove the barriers, raise the ceilings, unshackle the loyalties, release the energies and the initiative of this loyal race that together, all Americans, all liberty loving peoples may give their all that our way of life may survive.” 01:36-2:42 Mrs. Julia T. Glavin of Nashville, TN. “Mr. President, in this section of the United States it seems to me that there are two outstanding problems confronting us now. They have to do with our negro soldiers and taxation. In certain parts of our country the uniform of our army is not properly respected. Our loyal black boys in uniform should be protected while they’re in camp. The ruthless beating up and murdering of them should be stopped. This sort of thing breaks down the morale of any army. Every loyal soldier is an important factor in our defense program. It’ll take a lot of money to win this war. We’re going to win and we’re going to sacrifice all we have for our country, but it has become a problem to know how to meet these new taxes and keep up the old ones with our limited incomes which have not increased with the increased demand of heavy taxation. If we borrow we are plunged into debt, and citizens in debt cannot present as strong a defense as we desire, but we have pledged ourselves to do our best.”

"Dear Mr. President" Recorded Interview of Black Americans in Nashville, TN, 1942 00:08-01:31, 01:36-02:42 Recorded interviews with several Black Americans from Nashville, TN addressing President Roosevelt with their concerns regarding discrimination against black citizens and abuse of black servicemen. The Nashville residents interviewed asked President Roosevelt for his understanding and assistance in protecting the rights of black citizens to serve their country. Transcript: “...I am thinking of 15 million Negroes who are among the most loyal citizens in the United States. In the face of discrimination and segregation the Negro has remained loyal. What greater proof than a Joe Louis benefit for the navy, a branch of our armed services which has never permitted his race to rise above the ships galley. These millions of negroes are doing all in their power to serve in the presence crisis. Most defense industries are closed to him. The possibility of advancement in the army is definitely limited. If Democracy is to survive. If Democracy is ever to be made to work, our generation must make it work. We want as you do, to perpetuate the democratic way of life. Do all in your power as we are doing to remove the barriers, raise the ceilings, unshackle the loyalties, release the energies and the initiative of this loyal race that together, all Americans, all liberty loving peoples may give their all that our way of life may survive.” 01:36-2:42 Mrs. Julia T. Glavin of Nashville, TN. “Mr. President, in this section of the United States it seems to me that there are two outstanding problems confronting us now. They have to do with our negro soldiers and taxation. In certain parts of our country the uniform of our army is not properly respected. Our loyal black boys in uniform should be protected while they’re in camp. The ruthless beating up and murdering of them should be stopped. This sort of thing breaks down the morale of any army. Every loyal soldier is an important factor in our defense program. It’ll take a lot of money to win this war. We’re going to win and we’re going to sacrifice all we have for our country, but it has become a problem to know how to meet these new taxes and keep up the old ones with our limited incomes which have not increased with the increased demand of heavy taxation. If we borrow we are plunged into debt, and citizens in debt cannot present as strong a defense as we desire, but we have pledged ourselves to do our best.” "Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket Audio Jacket for "Dear Mr. President" interview of black residents in Nashville, TN during the winter of 1942.

"Dear Mr. President" Audio Recording Jacket Audio Jacket for "Dear Mr. President" interview of black residents in Nashville, TN during the winter of 1942. Sergeant Joseph H. Ward An announcement in The Oklahoma Eagle, a black newspaper, honoring the military service of Sgt. James H. Ward, recently transferred from Camp Howze, TX to Camp Claiborne, LA as a member of the U.S. Army Service Force.

Sergeant Joseph H. Ward An announcement in The Oklahoma Eagle, a black newspaper, honoring the military service of Sgt. James H. Ward, recently transferred from Camp Howze, TX to Camp Claiborne, LA as a member of the U.S. Army Service Force. "Dear Mr. President" by Miss Maude Gray In this recording, Miss Maude Gray of Austin, TX relays her concerns regarding the mistreatment and discrimination black soldiers, like her brother, were forced to endure as service members in the U.S. military. She asks President Roosevelt to understand that black Americans want to serve in the military honorably. She explains why black Americans need the president's help to ensure they are treated with dignity and offered the same opportunities to serve their country as all willing, able-bodied Americans. Transcript: Miss Maude Gray speaks about her brother and other black soldiers’ experience with racist treatment in the military and by authorities unwilling to hire them. “…I got a brother who’s in the army….when he left here he was mighty glad to get in the army. I don’t know whether he’s so glad to be there now from all the letters I’ve been gettin from him. Mind you, I don’t mean that he’s against our country or anything like that, but he’s not so satisfied with the treatment that he’s gettin up there, he thinks that it could be a little better….” The young woman goes on to describe degrading mistreatment of her brother and his fellow black soldiers. She mentions public fears of race riots as the justification for keeping black soldiers from accessing and training with weapons. “They don’t have any entertainment for them, whereas the white soldiers have lounges, and guest houses, and everything that they could wish for as far as facilities will permit while our boys don’t have anything but a post exchange. And that’s not very good for entertainment and when that’s all he has to do. I think they could stand that if they were just treated a little better when it comes to other things that are most important duties, promotions. The navy won’t let you in. The army, when they get you, it put you off somewhere off by yourself…”

"Dear Mr. President" by Miss Maude Gray In this recording, Miss Maude Gray of Austin, TX relays her concerns regarding the mistreatment and discrimination black soldiers, like her brother, were forced to endure as service members in the U.S. military. She asks President Roosevelt to understand that black Americans want to serve in the military honorably. She explains why black Americans need the president's help to ensure they are treated with dignity and offered the same opportunities to serve their country as all willing, able-bodied Americans. Transcript: Miss Maude Gray speaks about her brother and other black soldiers’ experience with racist treatment in the military and by authorities unwilling to hire them. “…I got a brother who’s in the army….when he left here he was mighty glad to get in the army. I don’t know whether he’s so glad to be there now from all the letters I’ve been gettin from him. Mind you, I don’t mean that he’s against our country or anything like that, but he’s not so satisfied with the treatment that he’s gettin up there, he thinks that it could be a little better….” The young woman goes on to describe degrading mistreatment of her brother and his fellow black soldiers. She mentions public fears of race riots as the justification for keeping black soldiers from accessing and training with weapons. “They don’t have any entertainment for them, whereas the white soldiers have lounges, and guest houses, and everything that they could wish for as far as facilities will permit while our boys don’t have anything but a post exchange. And that’s not very good for entertainment and when that’s all he has to do. I think they could stand that if they were just treated a little better when it comes to other things that are most important duties, promotions. The navy won’t let you in. The army, when they get you, it put you off somewhere off by yourself…” Miss Maude Gray, "Negro Girl from Austin, Texas" Jacket for the recording of Miss Gray in which she relays her concerns regarding the mistreatment and discrimination black soldiers, like her brother, were forced to endure as service members in the U.S. military. She asks President Roosevelt to understand that black Americans want to serve in the military honorably. She explains why black Americans need his help to ensure they are treated with dignity and offered the same opportunities as everyone else.

Miss Maude Gray, "Negro Girl from Austin, Texas" Jacket for the recording of Miss Gray in which she relays her concerns regarding the mistreatment and discrimination black soldiers, like her brother, were forced to endure as service members in the U.S. military. She asks President Roosevelt to understand that black Americans want to serve in the military honorably. She explains why black Americans need his help to ensure they are treated with dignity and offered the same opportunities as everyone else. Gainesville Negro Girl Lieutenant This brief mention of a young black woman's commission as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps was a rare moment of acknowledgment for black service members in news publications covering the local region surrounding Camp Howze

Gainesville Negro Girl Lieutenant This brief mention of a young black woman's commission as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps was a rare moment of acknowledgment for black service members in news publications covering the local region surrounding Camp Howze Response from Mr. Gibson,

Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War In this response letter to Private E.L. Reynolds, Mr. Gibson, implies that banning the Pittsburgh Courier, or any other "Negro publication" at Camp Howze would violate official War Department policy AG 461 Subject: Restriction of Commercial Publications. Mr. Gibson advises Pvt. Reynolds to write back with further details regarding this issue.

Response from Mr. Gibson,

Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War In this response letter to Private E.L. Reynolds, Mr. Gibson, implies that banning the Pittsburgh Courier, or any other "Negro publication" at Camp Howze would violate official War Department policy AG 461 Subject: Restriction of Commercial Publications. Mr. Gibson advises Pvt. Reynolds to write back with further details regarding this issue. Black Newspapers Banned at Camp Howze A letter from a black soldier at Camp Howze to Truman K. Gibson, Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War, in which the soldier asks why the camp's post exchange for black servicemen will not sell the Pittsburgh Courier, a highly regarded black newspaper. This was significant because news reports in local publications including the Camp Howze Howitzer rarely included stories of black citizens or service members, choosing instead to report exclusively on white Americans' experiences and perspectives that often demeaned black Americans.

Black Newspapers Banned at Camp Howze A letter from a black soldier at Camp Howze to Truman K. Gibson, Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War, in which the soldier asks why the camp's post exchange for black servicemen will not sell the Pittsburgh Courier, a highly regarded black newspaper. This was significant because news reports in local publications including the Camp Howze Howitzer rarely included stories of black citizens or service members, choosing instead to report exclusively on white Americans' experiences and perspectives that often demeaned black Americans. The Wolf - Untitled Camp Howze Howitzer Comic Racist imagery used for humor in the Camp Howze Howitzer.

The Wolf - Untitled Camp Howze Howitzer Comic Racist imagery used for humor in the Camp Howze Howitzer. "I Made $1.35 in Tips Yesterday" Racist depiction of African men dressed in loin cloth and carrying the white soldiers’ goods.

"I Made $1.35 in Tips Yesterday" Racist depiction of African men dressed in loin cloth and carrying the white soldiers’ goods. Camp Howze Howitzer Comic Comic illustration depicting a topless African woman looming over U.S. soldiers in a threatening manner.

Camp Howze Howitzer Comic Comic illustration depicting a topless African woman looming over U.S. soldiers in a threatening manner. Blackface Performance at Camp Howze Photo of servicemen from the 409th Infantry regiment dressed in blackface and costume posed to advertise a performance planned to entertain GIs at Camp Howze.

Blackface Performance at Camp Howze Photo of servicemen from the 409th Infantry regiment dressed in blackface and costume posed to advertise a performance planned to entertain GIs at Camp Howze. "Minstrel Darky Doings" Photograph of white servicemen from the 84th Infantry Division Special Service performing in blackface as minstrels to entertain GIs at Camp Howze.

"Minstrel Darky Doings" Photograph of white servicemen from the 84th Infantry Division Special Service performing in blackface as minstrels to entertain GIs at Camp Howze.